When I told people I was called to jury duty, most offered up advice on how to be excused—tell the judge you have a business trip, give biased answers to the attorneys questions during voi dire, have your doctor write you a note. A direct correlation developed between the frequency my peers were advising me to get dismissed and the strength in my assurance that I should serve.

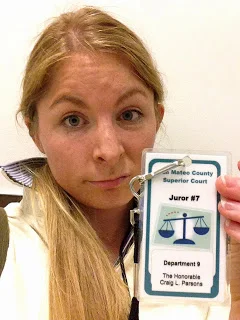

The morning of my jury duty, I joined several hundred of my peers in a room in the basement of the courthouse. We watched a video and were reminded of the importance of jury duty in our judicial system. I hopped on the WiFi and spent the next three hours working on my iPad waiting to be called to a courtroom or dismissed.

Shortly after lunch, the remaining 60 of us were called up to a courtroom. Then the complex game of selection began. Hardships were granted to those who had finals, pre-arranged business trips, and were not fluent in english. Those not granted hardships were then asked questions by the attorneys, at this time it became abundantly clear that the majority of full-time professionals had heard the advice about giving biased answers, and were quickly excused.

Four hours later, we had a final juror comprised of eleven women, one man and two female alternates. Two thirds of these jurors did not have college degrees and most worked clerical or service jobs. This is the county wherein Silicon Valley lies, but all of that education and diverse backgrounds were not represented in that jury box.

For the next three and a half days we sat through expert testimony regarding blood alcohol testing equipment, tolerance, rates of alcohol absorption, blood versus breath tests, field sobriety tests, and anything else you can imagine that pertains to drinking and driving. It was a tremendous amount of information, which seemed to be part of the defense's strategy-- overwhelm the juror's with information and hope that they convolute their inability to comprehend the specifics with reasonable doubt as it pertains to the specifics of this case.

When we finally began deliberations, it became clear that the task of understanding and logically applying the law to the facts of the case without contamination from sympathy and emotions was far too great for many of the jurors. When that small room became clouded with statements and questions like "He will be branded a criminal", "Thats not how I act when I'm drunk", "People should never drink and drive" I wanted to scream, "Objection! Outside the scope."

At the close of the first full day of deliberations I was consumed with sadness and frustration. Frustration that we had spent so much time discussing things that did not matter and talking in circles, and sad that the majority of this selection of my peers was either incapable or unaccustomed to critical thinking and logical reasoning.

Is this the endgame of an education system that places too much focus on self-esteem and participation instead of accountability and aptitude?

When debate ensued regarding the specifics of a juror's reasoning, the other juror's would often grow uncomfortable with the polite (and may I add necessary) debate and says things like, "I guess we are each entitled to our own opinions." While that may be true when it comes to subjective things like one's taste in movies or food. When it comes to jury duty, you are not entitled to opinions that are not grounded in facts and the law.

As much as I love Stephen Colbert, truthiness has gone too far. Our judicial system, economy, and society require people to be able to think with their head more often than they "know with their heart"-- or at least be able to tell the difference.